The Legacy of Freedman Town

Ashley Jordan February 2025

A legacy of resilience

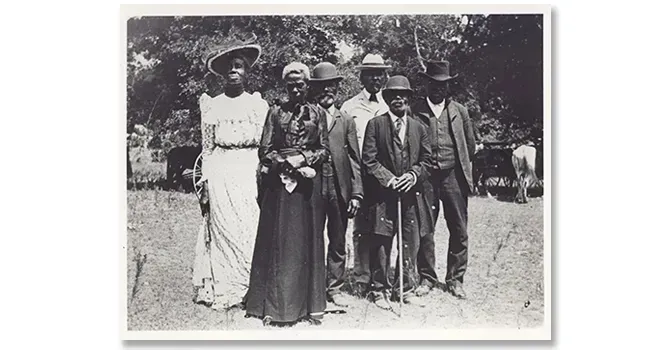

The history of Freedman Town, also known as North Dallas, stands as a powerful testament to the resilience and determination of African Americans in the aftermath of emancipation. Emerging in the wake of the Civil War, Freedman Town became a beacon of community, self-sufficiency, and cultural vibrancy for freed African Americans seeking refuge and opportunity in the rapidly developing city of Dallas.

Community Building After Emancipation in Freedman Town

Following emancipation in 1865, formerly enslaved African Americans across Texas sought new lives, leaving plantations to establish communities where they could build futures free from oppression. Freedman Town, located just two miles northeast of downtown Dallas, became one such haven. By 1873, the Dallas Herald recorded the presence of over 500 African Americans in the area, marking it as a thriving settlement.

Faced with systemic segregation, the residents of Freedman Town took it upon themselves to create a self-sufficient and tightly knit community. They founded institutions that addressed their immediate needs and nurtured long-term aspirations. Among the earliest were churches, which served as spiritual centers and hubs for social and educational activities. By 1878, Freedman Town boasted seven African American churches, including Bethel A.M.E., Evening Chapel, and St. Paul Methodist Episcopal. These institutions provided spiritual guidance and acted as schools and gathering spaces for the community.

Education was a cornerstone of Freedman Town's development. Churches hosted classes for children and adults alike, ensuring literacy and vocational skills spread throughout the community. Reverend Henry Swann of St. Paul M.E. Church and Reverend Allen R. Griggs of New Hope Baptist Church led initiatives that expanded access to education. Griggs, for example, established a grammar school in 1875, eventually growing it into a high school with a curriculum that included reading, arithmetic, geography, and Bible studies.

The residents of Freedman Town also pooled resources to develop economic opportunities. Early settlers purchased land, built homes, and established businesses to create a stable economic foundation. Notable figures like Dock Rowen and Abe Fuqua exemplified this entrepreneurial spirit, owning and managing businesses that served the community and ensured its financial independence.

Just to name a few among MANY remarkable individuals whose work shaped the community's cultural, economic, and educational landscape.

Dock Rowen

was a prominent entrepreneur who operated a successful grocery store and ran a real estate and loan business. In addition to selling wood and coal, Rowen was reportedly a stockholder in the founding of the State Fair of Texas in 1886. His home was located near present-day Ross Avenue, close to the intersection with Pearl Street, an area that now includes upscale apartments and retail spaces.

Abe Fuqua

A former cotton gin worker for William Caruth Sr., Fuqua became a notable landowner in Freedman Town. He owned multiple plots of land near what is now North Central Expressway and Hall Street. Fuqua’s home, an L-shaped structure, once stood near today’s Griggs Park, a space that still honors the Freedmantown legacy.

Reverend Allen R. Griggs

As the founder of New Hope Baptist Church, Reverend Griggs played a pivotal role in Freedman Town’s educational and spiritual life. His home, adjacent to the church, was located near what is now the intersection of Flora Street and Good-Latimer Expressway. This area is currently part of the Dallas Arts District.

Dr. Benjamin Bluitt:

A trailblazer in medicine, Dr. Bluitt operated one of Dallas's first Black-owned sanitariums in Deep Ellum. His residence, a two-story Victorian structure, was situated near present-day Elm Street and Good-Latimer Expressway, close to what is now a hub for entertainment and nightlife.

William Sydney Pittman

An influential architect and son-in-law of Booker T. Washington, Pittman designed several landmarks, including the St. James A.M.E. Church and the Knights of Pythias building. His Craftsman-style home was located on Good Street, now a part of the State-Thomas Historic District, which has transformed into a high-end residential and commercial area.

Reverend Henry Swann

As the pastor of St. Paul Methodist Episcopal Church, Reverend Swann led numerous educational efforts, including running a day school for local children. His home, near St. Paul’s location on Routh Street, is now part of the Uptown Dallas area, dominated by luxury high-rises and retail.

Norman W. Harllee:

A dedicated educator with a master's degree from the University of Chicago, Harllee was instrumental in advancing Black education in Freedmantown. He served as the principal of what became Booker T. Washington High School. His home was located near Flora Street and Olive Street, an area now part of the Dallas Arts District.

Alice J. Dunnegan

was a pioneering educator and civil rights advocate who founded the Dallas Women’s Club, one of the first Black women’s clubs in the city. She championed civil rights, focusing on segregation, voter disenfranchisement, and women’s suffrage. Her work empowered African American women and children in Dallas, leaving a lasting impact on the community and inspiring future generations of leaders.

Big Business

Dock Rowen’s Grocery Store and Real Estate Business

- A staple in Freedman Town's economic life, Dock Rowen provided essential goods and financial services.

- Modern Location: Near Ross Avenue and Pearl Street, now home to upscale apartments and retail shops.

Abe Fuqua’s Landholdings and Housing Ventures

- Fuqua owned and developed housing for Freedman Town residents.

- Modern Location: Near North Central Expressway and Hall Street, close to today’s Griggs Park.

Dr. Benjamin Bluitt’s Sanitarium

- One of the first Black-owned medical facilities in Dallas, offering healthcare to Freedman Town residents.

- Modern Location: Near Elm Street and Good-Latimer Expressway in the Deep Ellum district.

St. James Hotel and Lodging Businesses

- These establishments provided accommodations for Black travelers.

- Modern Location: Around Routh and Flora Streets, now part of the Dallas Arts District.

Knights of Pythias Building Businesses

- Housed offices for Black-owned law practices, insurance agencies, and event spaces.

- Modern Location: At Elm and Good Streets, formerly a vibrant community hub.

Barbershops, Salons and Tailor Shops

- These small businesses served as community centers and provided essential services.

- Modern Location: Concentrated near Griggs Park and the State-Thomas Historic District.

Church-Adjacent Markets and Stores

- Markets near churches like Free Mission Baptist provided daily necessities to residents.

- Modern Location: Around Hall Street and Cochran, an area now dominated by modern apartments.

Freedman’s Cemetery Memorial Businesses

- Businesses connected to the Freedman’s Cemetery supported burials and memorial services.

- Modern Location: Adjacent to the North Central Expressway near Lemmon Avenue.

What Remains.

The Freedman’s Cemetery, established in the 1860s by the community’s earliest settlers, served as the final resting place for countless African Americans in Freedman Town. Over time, the cemetery became a poignant symbol of the community’s perseverance and reverence for their ancestors. However, its fate was profoundly altered by urban development.

Broken plates represent broken families due to their loss.

Sea Shells to carry them back home to Africa.

Treasures from this life adorn the tops of their graves as reminders of who they were at the time of existence.

Freedman’s Cemetery is now part of Freedman’s Memorial Park, located near North Central Expressway and Lemmon Avenue. The park features sculptures, historical markers, and interpretive exhibits that pay tribute to the lives and contributions of the people interred there. Despite its transformation, the cemetery remains a vital symbol of Freedmantown’s legacy and the broader struggles of African Americans in Dallas.

This rediscovery shed light on the extent of the cemetery’s desecration and became a catalyst for efforts to honor and preserve the legacy of those buried there. Despite the recovery and relocation of some remains, it is believed that hundreds more graves remain unaccounted for due to incomplete historical records and the destruction caused by urban development.

During the highway expansion project in the late 1980s, approximately 1,500 graves were unearthed at Freedman’s Cemetery. Many of these graves had been unmarked or forgotten due to earlier construction efforts, such as the building of the North Central Expressway in the 1940s, which had already disrupted and paved over a significant portion of the cemetery.

Visit the African American Museum for a detailed Tour and Information

The City of Dallas and Urban Development in Freedman Town

The City of Dallas played a pivotal role in the urban development projects that reshaped Freedman Town, often at the expense of the African American community. These projects were driven by policies, decisions, and actions that prioritized infrastructure expansion and modernization over the preservation of historical and cultural landmarks.

Key Actions by the City of Dallas

Eminent Domain and “Blighted” Designations

- Starting in the early 20th century, the City of Dallas used eminent domain to acquire land in Freedman Town, categorizing the area as “blighted” or an “eyesore.” This designation allowed the city to displace residents under the guise of urban renewal.

- These policies disproportionately targeted Black neighborhoods, forcing many families to relocate and disrupting the social fabric of Freedman Town.

North Central Expressway Construction (1940s)

- The city collaborated with state and federal agencies to plan and construct the North Central Expressway, a major transportation artery. Freedman Town was in the direct path of this project.

- The expressway’s construction demolished homes, businesses, and community landmarks, including portions of Freedman’s Cemetery. Many graves were disturbed or paved over without adequate consultation or documentation.

Public Housing Projects

- In the 1940s, the City of Dallas approved the construction of the Roseland Homes public housing development in Freedman Town. While providing affordable housing, the project displaced numerous families and fundamentally altered the neighborhood’s character.

Urban Renewal and Redevelopment (1960s-1980s)

- During this period, the city pushed aggressive urban renewal initiatives that sought to modernize and gentrify areas near downtown Dallas. Freedman Town, now referred to as “State-Thomas” or “North Dallas,” became a focal point for redevelopment.

- The construction of the Woodall Rodgers Freeway in the 1960s dealt another blow to the community, severing connections to downtown Dallas and eliminating additional homes and businesses.

Historical Oversight

- Despite the area’s historical significance, the city failed to protect Freedman Town’s cultural heritage. The absence of preservation efforts contributed to the erasure of physical markers of the community’s past.

Key Players and Institutions Involved in Urban Development Plans

Planners and Officials

- Local planners spearheaded the designs for expressways and housing developments, often disregarding the impact on marginalized communities.

- Mayors and city council members during this time endorsed projects that prioritized economic growth and infrastructure expansion.

Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT)

- Partnered with the city to execute highway projects, including the North Central Expressway and Woodall Rodgers Freeway, that bisected Freedman Town.

Private Developers

- Developers collaborated with the city to acquire land for redevelopment projects. These ventures transformed Freedman Town into what is now Uptown, an affluent and predominantly white area.

Consequences of Urban Development

Freedman’s Cemetery Desecration

- The city’s failure to protect Freedman’s Cemetery during the construction of the North Central Expressway caused significant cultural and historical loss.

- Rediscovered in the 1980s, the cemetery became the focus of preservation efforts led by community advocates, resulting in the establishment of Freedman’s Memorial Park.

Gentrification of State-Thomas and Uptown

- Freedman Town evolved into the State-Thomas Historic District and later Uptown, characterized by high-end apartments, retail spaces, and entertainment venues.

- This gentrification erased much of Freedman Town’s original identity and displaced many of its descendants.

Ongoing Advocacy and Commemoration

- Activists, historians, and organizations continue to highlight the injustices of urban development and advocate for preserving the remaining traces of Freedman Town.

Moving Forward: A Vision for Healing and Reconciliation

To acknowledge Freedman Town’s legacy and move forward in a way that fosters healing without victimization or condemnation, we must take intentional steps to address historical injustices while building a shared narrative. Here's how:

1. Acknowledge the Past with Honesty

- Document and Share Freedman Town’s History: Through museums, public art, digital archives, and school curricula, ensure that the story of Freedman Town is told authentically and without erasure.

- Recognize Contributions: Highlight the achievements and resilience of Freedman Town’s residents, framing their story as one of empowerment and ingenuity despite systemic oppression.

2. Invest in the Cultural Narrative

- Establish a Cultural Center: Create a dedicated space for Freedman Town’s history, featuring artifacts, oral histories, and educational programs.

- Memorialize with Public Art: Expand initiatives like Freedman’s Memorial Park with monuments, murals, or art installations to commemorate the community’s contributions and sacrifices.

- Support Black Artists and Scholars: Fund projects that explore Freedman Town’s legacy and its impact on Dallas and beyond.

3. Build Bridges Across Communities

- Community Dialogues: Host forums where residents, historians, and stakeholders can engage in conversations about Freedman Town, addressing its history, impact, and ongoing relevance.

- Partnerships Between Neighborhoods: Encourage collaboration between Uptown residents, local businesses, and community leaders to create inclusive initiatives that honor Freedman Town’s legacy.

4. Reinvest in Equity

- Affordable Housing Initiatives: Dedicate resources to housing programs that serve historically displaced families and ensure that descendants of Freedman Town’s residents have opportunities to live and thrive in Dallas.

- Economic Empowerment: Offer grants, mentorship, and spaces for Black entrepreneurs and businesses, particularly in areas historically tied to Freedman Town.

- Education and Scholarship Funds: Establish scholarships for students from historically underrepresented communities, naming them after Freedman Town’s pioneers.

5. Create Opportunities for Healing

- Intergenerational Healing Programs: Facilitate workshops and events that allow descendants of both Freedman Town residents and those connected to its displacement to share their stories and find common ground.

- Inclusive Events: Organize events like Juneteenth celebrations, cultural festivals, and historical reenactments that bring diverse communities together to celebrate Freedman Town’s legacy.

6. Foster Long-Term Accountability

- City-Led Reparative Actions: Encourage the City of Dallas to issue formal acknowledgments of harm done to Freedman Town and commit to reparative initiatives, such as funding cultural preservation or community redevelopment.

- Historical Preservation Ordinances: Implement policies to protect remaining Freedman Town landmarks and ensure that no further erasure of historical sites occurs.

A Shared Commitment

By embracing this multifaceted approach, we can honor Freedmantown without perpetuating cycles of blame or division. This path acknowledges the past while forging a future rooted in equity, collaboration, and remembrance. It is not about assigning guilt but about fostering understanding, healing, and a shared commitment to justice.

It's time for a new adventure in creativity!

Get ready to experience your newest passion.

Join a Class